How fair is a fair? People-powered decision-making at the Petaluma Fairgrounds

Peggy Flynn is the city manager for Petaluma and can be reached at PFlynn@cityofpetaluma.org. Alex Renirie is the program co-director for Healthy Democracy and can be reached at alex@healthydemocracy.org.

It’s no secret that cities are falling prey to the same bitter, adversarial politics that dominate national politics. What were once safe havens for neighbor-to-neighbor collaboration are fracturing. And the voices that dominate public conversations are still disproportionately older, white, and wealthier. But a new form of democracy is lighting a path forward — one that counters polarization head-on and represents our diverse and culturally complex communities.

The tools we need to transform contentious community issues into a creative collaboration where all people are seen and heard are within reach. One powerful example is the Petaluma Fairgrounds Advisory Panel.

What is people-powered decision-making?

Public trust in the federal government has returned to historic record lows following a modest uptick in 2020 and 2021. Only one percent of Americans say they trust the federal government to do what is right “just about always” according to Pew Research. This is among the lowest trust measures in nearly seven decades of polling.

We feel this at the local level too. How often do we decry the apathy or disengagement of our residents? Many cities have invested significant resources into new types of community engagement. Yet the cycle of disillusionment, cynicism, and disconnection continues. Our communities don’t see themselves in public decision-making and therefore aren’t invested in the outcome. Many people are too tired, under-resourced, or intimidated to help make decisions that affect their day-to-day lives.

There is no magic bullet for disengagement. But governments around the world are experimenting with ways to make local decision-making work without dramatic new investments. Lottery-selected panels, or Citizens’ Assemblies, are one such example. These 50-year-old democratic innovations can counter rampant polarization and political elitism by transforming who participates in decision-making and how decisions get made.

The model has been used over 600 times globally as a way for governments to engage residents in collaborative, inclusive, and informed policy decisions While varied in size, scope, and task, these panels always combine two core elements: Enlist a random group of people who reflect the place’s demographics and provide them with tools to make thoughtful decisions — extensive information, a detailed process, and a lot of time. They often reach supermajority agreements on topics that elected officials are unable to solve and their detailed recommendations are adopted at high rates.

These panels are uniquely positioned to examine hot-button policy issues with independence and rigor. In other words, the process is the exact opposite of politics as usual.

The Petaluma Fairgrounds Advisory Panel

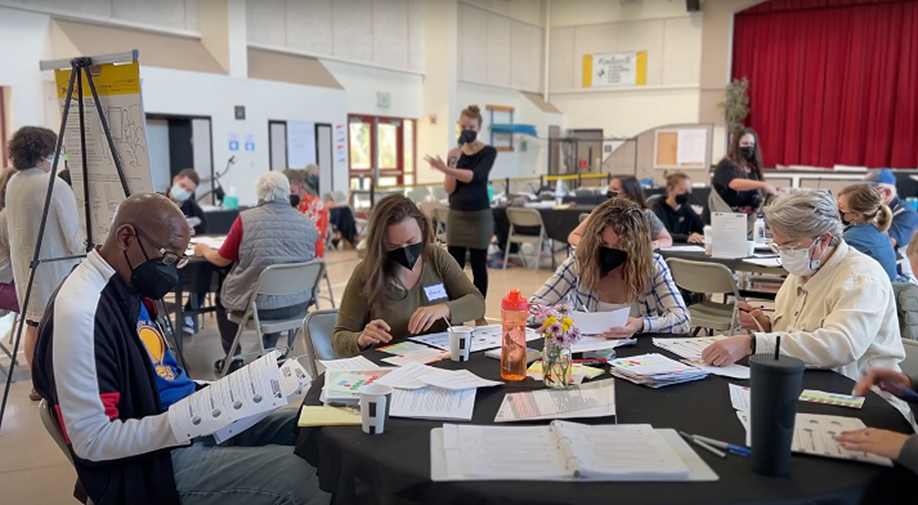

The Petaluma Fairgrounds Advisory Panel is the most intensive lottery-selected panel process convened in the U.S. Thirty-six Petalumans — aided by Health Democracy, a nonpartisan nonprofit — helped shape the fate of one of the city’s most beloved properties.

Of course, the future use of a valuable city-owned property was not without its controversy. The Sonoma-Marin Fairgrounds property had hosted the agricultural community, local businesses, schools, and other community services for decades. Planning for the site — mired in decades-long conflict — was at a crossroads.

The city (pop. 60,000) faced tensions that mirrored some of the hottest policy debates in California. How could the city meet the needs of a growing, diverse population while honoring the area’s rich agricultural roots? How could it preserve green space to increase climate resiliency and improve folks’ quality of life, while addressing an out-of-control housing crisis?

Traditional engagement would only create more adversarial stalemates. Politics-as-usual risked a continued lack of representation among people of color, youths, renters, and other marginalized populations. So in 2022, the city council unanimously voted to try a lottery-selected panel.

Unlike typical advisory boards, this panel was made up of residents with no prior involvement with the property or with the city. Healthy Democracy used a democratic lottery to select a random cross-section of city residents that reflected the city’s demographics (race/ethnicity, gender, age, educational attainment, geography, housing status, and experience of a disability).

The city took this process one step further by using equity-driven selection targets. Most democratic lotteries establish selection targets based on equality. If 60% of a population rents, then renters will make up exactly 60% of the panel. But in this case, we over-selected groups based on the rates they had been underrepresented in past city processes.

For instance, renters were 34% of the Petaluma population but made up 19% of past participants at events related to the fairground’s future. Therefore, we gave renters 49% of the 36 seats on the panel. Equity-driven selection is just one way to account for complex histories of exclusion in public policymaking.

Healthy Democracy also mitigated barriers to participation by giving panelists stipends equal to a fair hourly wage, child and eldercare reimbursements, and comprehensive language services. Around 80% of the program’s approximately $450,000 costs went directly to compensate or support the panel.

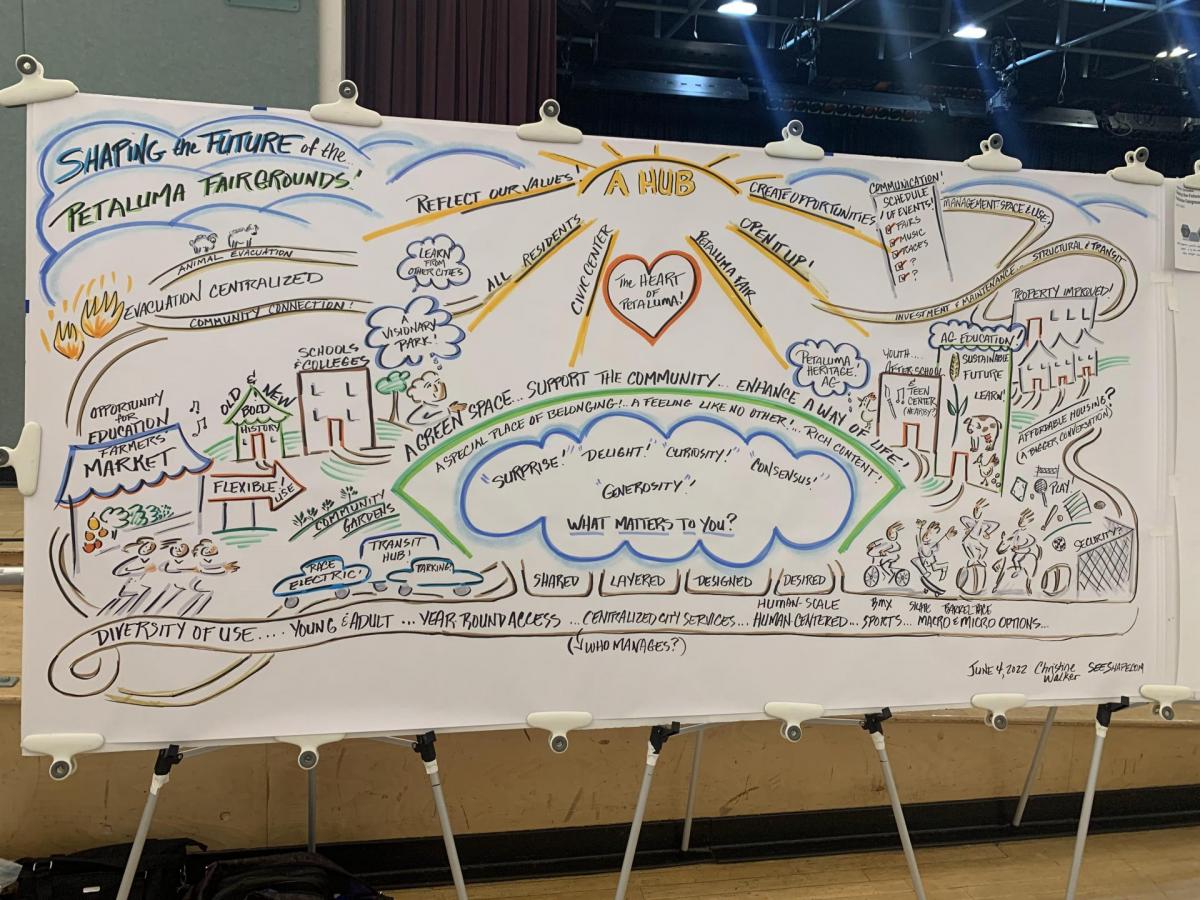

Panelists examined many perspectives and policy proposals and heard from dozens of presenters — selected in part by the panelists. The panelists also hosted a listening session with the broader community and reviewed ideas collected by surveys.

“Being inclusive of all of our demographics and being able to sit and listen and appreciate what is needed for the community has been beneficial not just for me as a resident for 11 years in Petaluma but I think for the whole community,” said Mary, one of the panelists.

A team of professional moderators guided the process, mostly in small group settings. Panelists spent hours building their capacity for critical thinking, mitigating power imbalances in group settings, and practicing collaborative problem-solving. (This was more training than some elected officials will ever receive!)

The panel coalesced around three detailed visions for the property — including supermajority recommendations. The city council adopted those recommendations as eight guiding principles to ensure the community’s needs and desires are reflected in any activity, improvement, and planning effort that occurs on the property.

But the impact of this panel goes beyond the fairgrounds. Since then, the group has remained involved in other local issues. “My experiences have been not only getting to know other Petalumans but getting to know and understand how democracy works or could work in a more functional way,” said Jason, another panelist.

The wider community also saw value in the lottery-selected process. In a survey of the broader community, a little over half thought the recommendations would have an impact on the fairground’s final development. And they were right.

The panel’s recommendations enjoyed broad community support. Even adversarial community members bought into the process and expressed appreciation to the panel for identifying win-win land use recommendations. Selection by lottery strengthened the credibility of the recommendations because the voices of panelists weren’t from the expected advocates on either side of the issue.

“It has been a huge commitment, and it was a big leap into another way of working together,” said Teresa Barrett, the city’s former mayor. “This process seems to move to collaboration from competition, and I think that’s the only way we move forward.”

Where next?

Lottery-selected democracy is no panacea, but it is an example of a complex design that directly counters many of the threats facing our democracy today. It guarantees representation of many identities rather than relying on those who have the time, confidence, and resources to show up. It fosters collaboration more concretely than one-directional community engagement. And it fundamentally shifts power to communities.

If our goal is to protect community-scale collaborative infrastructure, we must rediscover and improve creative tools for decision-making. We can’t continue using the same methods hoping that new people will show up or that we can achieve a wholly new outcome. We cannot upend our fractured systems without good processes that encourage us to do so.

A previous, more in-depth version of this article appeared in the National Civic Review. We are grateful for the opportunity to share it here.